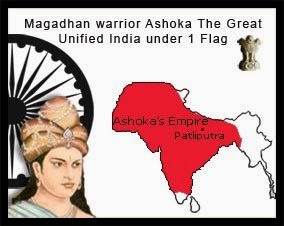

The great emperor of india- ASHOKA

Ashoka, the Mauryan Emperor, looked at the bodies strewn around the smashed city, and at the Daya River that ran red with blood. He was surveying the damage that his army had inflicted on the recalcitrant Kalinga region. About 100,000 civilians were dead, as well as 10,000 of Ashoka's soldiers.

Far from feeling the glorious rush of victory, Ashoka felt sick and saddened. He vowed that never again would he rain down death and destruction on other people. He would devote himself to his Buddhist faith and practice ahimsa, or nonviolence.

This story and many others about a great emperor called Ashoka appear in ancient Sanskrit literature, including the Ashokavadana, Divyavandana, and Mahvamsa. For many years, westerners considered them to be mere legend. They did not connect the ruler Ashoka, grandson of Chandragupta Maurya, to the stone pillars inscribed with edicts that are sprinkled all around the edges of India.

In 1915, however, archaeologists found a pillar inscription that identified the author of those edicts, the well-known Mauryan emperor Piyadasi or Priyadarsi ("Beloved of the Gods"), by his given name. That name was Ashoka. The virtuous emperor from the ancient texts, and the law-giver who ordered the installation of pillars inscribed with merciful laws all over the subcontinent - they were the same man.

Ashoka's Early Life:

In 304 BCE, the second emperor of the Maurya Dynasty, Bindusara, welcomed a son into the world. The boy's mother Dharma was only a commoner, and he had several older half-brothers, so he seemed unlikely to ever rule. This baby was named Ashoka Bindusara Maurya.

Ashoka grew up to be a bold, troublesome and cruel young man. He was extremely fond of hunting; according to legend, he even killed a lion using only a wooden stick. His older half-brothers feared Ashoka and convinced his father to post him as a general to distant frontiers of the Mauryan Empire. Ashoka proved a competent general, likely much to his brothers' dismay, putting down a rebellion in the Punjabi city of Taxshila.

Aware that his brothers viewed him as a rival for the throne, Ashoka went into exile for two years in the neighboring country of Kalinga. While there, he fell in love with a commoner, a fisherwoman named Kaurwaki. The two later married.

Bindusara recalled his son to Maurya after two years to help quell an uprising in Ujjain, the former capital of the Avanti Kingdom. Ashoka succeeded but was injured in the fighting. Buddhist monks tended to the wounded prince in secret, so that his eldest brother, the heir apparent Susima, would not learn of Ashoka's injuries. Their patient learned the basic tenets of Buddhism from them. A woman from Vidisha called Devi also attended Ashoka during this period - he fell in love with her and married her.

When Bindusara died in 275 BCE, a two-year-long war for the succession erupted between Ashoka and his half-brothers. The Vedic sources vary on how many of Ashoka's brothers died; one says that he killed them all, while another states that he killed several of them. In either case, Ashoka prevailed and became the third ruler of the Mauryan Empire.

"Chandashok," or Ashoka the Terrible:

For the first eight years of his reign, Ashoka waged near-constant war. He had inherited a sizable empire, but he expanded it to include most of the Indian subcontinent, as well as the area from the current-day borders of Iran and Afghanistan in the west to Bangladesh and the Burmese border in the east. Only the southern tip of India and Sri Lanka remained out of his reach, plus the kingdom of Kalinga on the northeast coast of India.

In 265, Ashoka attacked Kalinga. Although it was the homeland of his second wife, Kaurwaki, and the king of Kalinga had sheltered Ashoka before his ascent to the throne, the Mauryan emperor gathered the largest invasion force in Indian history to that point and launched his assault. Kalinga fought back bravely, but in the end it was defeated, and all of its cities sacked.

Ashoka had led the invasion in person, and he went out into the capital city of the Kalingas the morning after his victory to survey the damage. The ruined houses and bloodied corpses sickened the emperor, and he underwent a religious epiphany. Although he had considered himself more or less Buddhist prior to that day, the carnage at Kalinga led Ashoka to devote himself to Buddhism. He vowed to practice ahimsa from that day forward.

Ashoka the Great:

Had Ashoka simply vowed to himself that he would live according to Buddhist principles, later ages would not remember his name. However, he published his intentions across his empire. Ashoka wrote out a series of edicts, explaining his policies and aspirations for the empire, and urging others to follow his enlightened example.

The Edicts of King Ashoka were carved onto pillars of stone 40 to 50 feet high and set up all around the edges of the Mauryan Empire as well as in the heart of Ashoka's realm. Dozens of these pillars dot the landscapes of India, Nepal, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

In his edicts, Ashoka vows to care for his people like a father. He promises neighboring people that they need not fear him; he will use only persuasion, not violence, to win people over. Ashoka notes that he has made available shade and fruit trees for the people, as well as medical care for all people and animals.

His concern for living things also appears in a ban on live sacrifices and sport hunting. Ashoka urges his people to follow a vegetarian diet and bans the practice of burning forests or agricultural wastes that might harbor wild animals. A long list of animals appears on his protected species list, including bulls, wild ducks, squirrels, deer, porcupines, and pigeons.

Ashoka also ruled with incredible accessibility. He notes that "I consider it best to meet with people personally." To that end, he went on frequent tours around his empire. He also advertised that he would stop whatever he was doing if a matter of imperial business needed attention - even if he was having dinner or sleeping, he urged his officials to interrupt him.

In addition, Ashoka was very concerned with judicial matters. His attitude toward convicted criminals was quite merciful. He banned punishments such as torture, the putting out of people's eyes, and the death penalty. He urged pardons for the elderly, those with families to support, etc.

Another principle that Ashoka stressed in his edicts was respect for others. He recommends treating not just parents, teachers and priests with respect, but also friends and even servants.

Finally, although Ashoka urged his people to practice Buddhist values, he fostered an atmosphere of respect for all religions. Within his empire people followed not only the relatively new Buddhist faith, but also Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Greek polytheism and many other belief systems. Ashoka served as an example of tolerance for his subjects, and his religious affairs officers encouraged the practice of any religion.

Ashoka's Legacy:

Ashoka the Great ruled as a just and merciful king from his epiphany in 265 until his death in 232 BCE, at the age of 72. We no longer know the names of most of his wives and children. However, his twin children by his first wife, a boy called Mahindra and a girl named Sanghamitra, were instrumental in converting Sri Lanka to Buddhism.

After Ashoka's death, the Mauryan Empire continued to exist for 50 years, but it went into a gradual decline. The last Mauryan emperor was Brhadrata, who was assassinated in 185 BCE by one of his generals, Pusyamitra Sunga.

Although his family did not rule for long after he was gone, Ashoka's principles and his examples lived on through the Vedas. He is now known the world over as one of the best rulers ever to have reigned.

Sources:

"The Edicts of Ashoka," trans. Ven. S. Dhammika (Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka

Emperor Ashoka the Great (sometimes spelt Aśoka) lived from 304 to 232 BCE and was the third ruler of the Indian Mauryan Empire, the largest ever in the Indian subcontinent and one of the world's largest empires at its time. He ruled form 268 BCE to 232 BCE and became a model of kingship in the Buddhist tradition. Under Ashoka India had an estimated population of 30 million, much higher than any of the contemporary Hellenistic kingdoms. After Ashoka’s death, however, the Mauryan dynasty came to an end and its empire dissolved.

The Government of Ashoka

In the beginning, Ashoka ruled the empire like his grandfather did, in an efficient but cruel way. He used military strength in order to expand the empire and created sadistic rules against criminals. A Chinese traveller named Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang) who visited India for several years during the 7th century CE, reports that even during his time, about 900 years after the time of Ashoka, Hindu tradition still remembered the prison Ashoka had established in the north of the capital as "Ashoka’s hell". Ashoka ordered that prisoners should be subject to all imagined and unimagined tortures, and nobody should ever leave the prision alive.

During the expansion of the Mauryan Empire, Ashoka led a war against a feudal state named Kalinga (present day Orissa) with the goal of annexing its territory, something that his grandfather had already attempted to do. The conflict took place around 261 BCE, and it is considered one of the most brutal and bloodiest wars in world history. The people from Kalinga defended themselves stubbornly, keeping their honour but losing the war: Ashoka’s military strength was far beyond Kalinga’s. The disaster in Kalinga was supreme: with around 300,000 casualties, the city devastated, and thousands of surviving men, women and children deported.

India was turned into a prosperous and peaceful place for years to come.

What happened after this war has been subject to numerous stories and it is not easy to make a sharp distinction between facts and fiction. What is actually supported by historical evidence is that Ashoka issued an edict expressing his regret for the suffering inflicted in Kalinga and assuring that he would renounce war and embrace the propagation of dharma. What Ashoka meant by dharma is not entirely clear: some believe that he was referring to the teachings of the Buddha and, therefore, he was expressing his conversion to Buddhism. But the word dharma, in the context of Ashoka, had also other meanings not necessarily linked to Buddhism. It is true, however, that in subsequent inscriptions Ashoka specifically mentions Buddhist sites and Buddhist texts, but what he meant by the word dharma seems to be more related to morals, social concerns and religious tolerance rather than Buddhism.

The Edicts of Ashoka

After the war of Kalinga, Ashoka controlled all the Indian subcontinent except for the extreme southern part and he could have easily controlled that remaining part as well, but he decided not to. Some versions say that Ashoka was sickened by the slaughter of the war and refused to keep on fighting. Whatever his reasons were, Ashoka stopped his expansion policy and India turned into a prosperous and peaceful place for the years to come.

Ashoka began to issue one of the most famous edicts in the history of government and instructed his officials to carve them on rocks and pillars, in line with the local dialects and in a very simple fashion. In the rock edicts, Ashoka talks about religious freedom and religious tolerance, he instructs his officials to help the poor and the elderly, establishes medical facilities for humans and animals, commands obedience to parents, respect for elders, generosity for all priests and ascetic orders no matter their creed, orders fruit and shade trees to be planted and also wells to be dug along the roads so travellers can benefit from them.

However attractive all these edicts might seem; the reality is that some sectors of Indian society were truly upset about them. Brahman priests saw in them a serious limitation to their ancient ceremonies involving animal sacrifices, since the taking of animal life was no longer an easy business and hunters along with fishermen were equally angry about this. Peasants were also affected by this and were upset when officials told them that "chaff must not be set on fire along with the living things in it". Brutal or peaceful, it seems that no ruler can fully satisfy the people.

The Patronage of Buddhism

The Buddhist tradition holds many legends about Ashoka. Some of these include stories about his conversion to Buddhism, his support of the monastic Buddhist communities, his decision to establish many Buddhist pilgrimage sites, his worship of the bodhi tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment, his central role organizing the Third Buddhist Council, followed by the support of Buddhist missions all over the empire and even beyond as far as Greece, Egypt and Syria. The Buddhist Theravada tradition claims that a group of Buddhist missionaries sent by Emperor Ashoka introduced the Sthaviravada school (a Buddhist school no longer existent) in Sri Lanka, about 240 BCE.

It is not possible to know which of these claims are actual historical facts. What we do know is that Ashoka turned Buddhism into a state religion and encouraged Buddhist missionary activity. He also provided a favourable climate for the acceptance of Buddhist ideas and generated among Buddhist monks certain expectations of support and influence on the machinery of political decision making. Prior to Ashoka Buddhism was a relatively minor tradition in India and some scholars have proposed that the impact of the Buddha in his own day was relatively limited. Archaeological evidence for Buddhism between the death of the Buddha and the time of Ashoka is scarce; after the time of Ashoka, it is abundant.

Was Ashoka a true follower of the Buddhist doctrine or was he simply using Buddhism as a way of reducing social conflict by favouring a tolerant system of thought and thus make it easier to rule over a nation composed of several states that were annexed through war? Was his conversion to Buddhism truly honest or did he see Buddhism as a useful psychological tool for social cohesion? The intentions of Ashoka remain unknown and there are all types of arguments supporting both views.

Ashoka’s Legacy

The myths and stories about Ashoka propagating Buddhism, distributing wealth, building monasteries, sponsoring festivals, and looking after peace and prosperity served as an inspiring model of a righteous and tolerant ruler that influenced monarchs from Sri Lanka to Japan. A particular story saying that Ashoka built 84,000 stupas (commemorative Buddhists buildings used as a place of meditation), served as an example to many Chinese and Japanese rulers who imitated Ashoka’s initiative.

He did with Buddhism in India what Emperor Constantine did with Christianity in Europe and what the Han dynasty did with Confucianism in China: he turned a tradition into an official state ideology and thanks to his support Buddhism ceased to be a local Indian cult and began its long transformation into a world religion. Eventually Buddhism died out in India sometime after Ashoka’s death, but it remained popular outside its native land, especially in eastern and south-eastern Asia. The world owes to Ashoka the growth of one of the world’s largest spiritual traditions.

Comments

Post a Comment